Loooong Webcomic Recommendations

Hallooo there! Anybody still around? Now that the frightening deadline for grades closing has arrived, it’s safe once again to use the internet for a playground. I thought I’d take a tip from Emily and start a webcomic’s thread to compliment the print recommendations. Please add your own too!

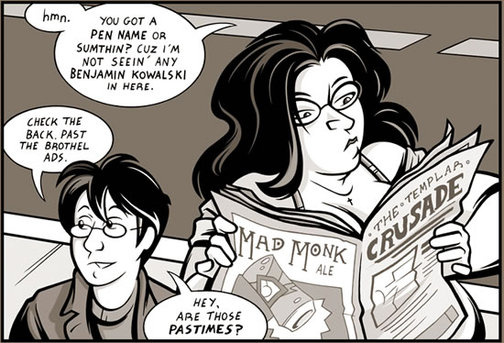

Templar Arizona: http://templaraz.com (watch out, the current page is NSFW)

Spike’s brilliantly drawn and written comic follows an engagingly odd cast of characters led by the shy aspiring writer and adult runaway Ben Kowalski as they go about their lives in the fictional city of Templar. Spike has described the setting of Templar, Arizona as “a slightly irregular Arizona that fell off the back of a truck somewhere, and now all the power outlets are a weird shape and a couple of wars never happened.” The city is a character in itself, and half the fun of the comic is finding out more about the bizarre cultural subgroups and cults that have sprouted up (like the Sincerists, who vow to never tell anything but the absolute truth, the historical enthusiasts Pastimes, the mysterious mute Wickerheads, the apocalyptic mystic Jakeskins, the Nile Revivalists…and on and on and on!). Currently in progress but seems to be going into its final arc.

Spike’s brilliantly drawn and written comic follows an engagingly odd cast of characters led by the shy aspiring writer and adult runaway Ben Kowalski as they go about their lives in the fictional city of Templar. Spike has described the setting of Templar, Arizona as “a slightly irregular Arizona that fell off the back of a truck somewhere, and now all the power outlets are a weird shape and a couple of wars never happened.” The city is a character in itself, and half the fun of the comic is finding out more about the bizarre cultural subgroups and cults that have sprouted up (like the Sincerists, who vow to never tell anything but the absolute truth, the historical enthusiasts Pastimes, the mysterious mute Wickerheads, the apocalyptic mystic Jakeskins, the Nile Revivalists…and on and on and on!). Currently in progress but seems to be going into its final arc.

Anders Loves Maria: http://anderslovesmaria.reneengstrom.com/2006/09/11/2006-09-11/ (also frequently NSFW)

In the words of its creator, Rene Engstrom: “It is a story about “adulthood” in a modern age where coming-of-age seems to be completely arbitrary.” It’s funny, foul, raunchy, and heartbreaking. It’s wildly experimental with chaning art styles to suit emotional moods. It’s also almost finished so go caught up!

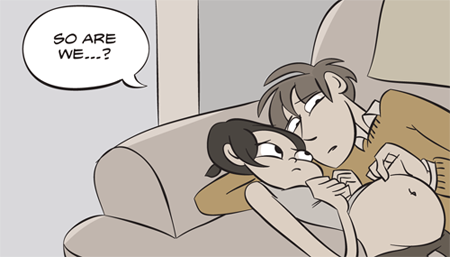

Octopus Pie: http://www.octopuspie.com/

Impeccably drawn comic following the adventures and misadventures of a couple of twenty-somethings living in New York, centering around the surly, practical Everest Ning and her roommate and former kindergarten friend, professional stoner Hanna. Everything is just a little on the weird side of normal but all the emotions ring true. Meredith Gran writes in neat storylines so hop on wherever catches your eye to see if you like it.

Just add on any webcomic recommendations you have, and happy vacation to all!

proxies

Exit Wounds, Jimmy Corrigan, and Ghost World’s main characters all shared a peculiar quality: they all used each other as sexual or emotional proxies. Koby and Numi were only brought together by the search for Gabriel. Koby both envies and resents the glimpses of sweetness of his father that he hears about from Numi, and Numi only ropes Koby into her search for Gabriel because she wants to prove that he didn’t leave, and that he died instead. In fact, they’re only brought together because of Gabriel, and it doesn’t matter that we never actually meet him; all that matters is that this charismatic man has affected the lives of so many people in such a way that some of them seem driven to craziness when they feel his absence.

In fact, the tension surrounding the idea of Gabriel comes to a head when Numi says to Koby, “Like father, like son,” during sex. Yes, it’s an extremely strange comment, and it’s no surprise that Koby reacts so angrily. The comparison of father and son here is what drives Koby and Numi apart, but in Jimmy Corrigan, the death of Jimmy’s dad is what drives apart Jimmy and his ‘adopted’ sister Amy. Jimmy wants to be normal like Amy, and to have a relationship built upon years of familiarity and love with his father like Amy does. Amy, on the other hand, is obviously different because of her race, and would love to be a blood relative of the Corrigans. The irony, of course, is that Amy actually is related to the Corrigans, and Jimmy doesn’t realize how similar his lonely life is to that of his grandfather (or at least his childhood).

Lastly, although Enid and Rebecca are very close friends, they also hurt each other through their comments to each other, or by ignoring the other’s wishes. Being teenage girls, one of the stressors in their friendship is their relative attractiveness to the opposite sex, each frequently telling the other that the other is much hotter. Because of this, perhaps the most literal way they hurt each other is through the character of Josh, who Enid goes to have sex with after feeling betrayed by Rebecca, but it’s Rebecca who ends up in a relationship with Josh; Clowes shows this in a way that led me to believe that Rebecca was the one who betrayed Enid. It also seems like this was one of the forces that drew them apart in the end; Rebecca is shown getting off work and leaving to hang out with Josh, not Enid. And at the end, Rebecca and Josh are shown sitting together in the diner, with Enid sadly but admirably looking on. This situation is somewhat different from the others because Josh serves as a proxy for both characters to try to hurt each other, not to get closer to each other. Still, I’m left thinking that all these proxy relationships serve to contrast the main characters with each other, and perhaps make them foils for one another.

Graphic Novel Recommendations

Hello All! I realized that no one had shared their graphic novel recs and thought I’d attempt to start a thread on that. I would like to recommend the “Scott Pilgrim” series by Bryan Lee O’Malley. Sharp, witty, and hilarious, these comics follow our main character/hero Scott Pilgrim, a Canadian 20-something attempting to start life as an adult and woo the lovely Ramona Flowers. There’s a twist, though: if he wants to date her, he first has to defeat her seven evil ex-boyfriends. Here’s a link: http://www.scottpilgrim.com/

I’d love to hear other suggestions, if anyone wants to share!

Ivorian Bonus

I found the glossary and tutorials at the end of Aya the most interesting aspect of the graphic novel. First because the glossary was meant to inspire a closer reading of the text, and second because it adds to the sensory experience of this colorful comic. Each of the pages is associated with an appropriate character from the novel; Aya, a girl with aspirations to go to college gives a list of terms and definitions, Adjoua explains the cultural significance of the pagne, etc. Ignace reveals a secret at the end of the book that takes the reader within his confidences as he shares his knowledge about gnamankoudji, a stark difference from the beginning of the comic in which Ignace seems to laud the “strong man’s” beer (1). Without Bintou, the tassaba roll would seem forced and extraneous and the peanut sauce recipe would lack significance in the scope of the story if it was simply the authors that decided that the recipe would represent the flavors of the Ivory Coast.

The glossary defies my expectations since it places the comic medium between strict literature and film- a glossary of terms usually illuminates text in an academic fashion, but in a format in which the text is simultaneously digested with images, the terms procure an involvement with the images and feelings displayed within the novel. For example, the explanation of the pagne invites the readers to inspect the different designs carefully in order to explicate the personalities of the pagne’s bearers. Aya, on page 16, sports a blue pagne with tooth-like white streaks similar to a tiger’s coat. In another sequence, she wears a pagne with yellow zigzags streaking down a purple background (48). Even though Adjoua explains these caustic designs at the end of the story, I am left to wonder if my initial reading of the story had been influenced to a greater degree by the color schemes that Oubrerie included within the story. A closer inspection reveals that these pagne are vibrant designs set against a nuanced rich and dull backgrounds of color. This leaves the reader to ruminate on the importance of pagne in the Ivory Coast, the importance of corporeal/visual representations of sexuality and identity. Even the tassaba roll evokes the “illusion” of movement within the panels, simply because the swaying of the hips becomes a symbol of femininity and grace. The tassaba tutorial implies that the dance on page 11 has much heavier movement, speed, and light-heartedness than the picture represents.

My favorite part of the “Ivorian Bonus” is the recipe, simply because I can visualize the time and effort it takes to prepare the peanut sauce. Like a cookbook, it lists ingredients and procedures complemented with images, but its hand-drawn nature expresses a genuine “home cooked” vibe. The total preparation time takes 85 minutes and each step in the cooking process links the readers senses to the actions at hand.

Ghost World

The pages of Daniel Clowes’ Ghost World are filled with the suburban adventures of bored best friends Enid Closeslaw and Rebecca Doppelmeyer. Their dead-end town remains unnamed for the entire book, and becomes quite relatable for every kid that feels stuck in a town too small for them. Enid and Rebecca banter incessantly and their cynical personalities lead them to constantly critique popular culture. But as they grow out of their adolescence, tensions arise and the two drift apart. Clowe’s graphic novel is a stark representation of adolescent life and the sadness that can accompany growing up.

It is possible that Ghost World struck me most of all the novels we studied this semester in class. The unnamed town that our heroines live in is not unlike the one I spent my adolescence. Shopping malls and fast food restaurants were where my friends and I would spend the majority of our free time. Just like Enid, my boredom would lead me to seek cheap thrills (Enid forced Josh to take her to a pornographic store, I forced my friends to make Maltov Cocktails out of empty bottles to throw on our high school’s baseball diamond).

The ease in which I related to the characters (or imagined someone else relating to the characters—is there a word for this?) was interesting to me. While I found more similarities with Enid (a bit eccentric and fascinated with weird things), I could see many readers finding similarities with Rebecca. She assumes the role of a more typical teenage girl character—the type that reads teen magazines. At the end of the novel, she also ends up on a more normal trajectory, maturing into a potentially sensible woman. Enid, on the other hand fails to gain admission into college and leaves town to start a new life. The melancholy that this separation brings is poignant, especially because of the familiarity of the setting and characters.

The art complements this dreary and profoundly realistic story. The characters are average looking (erring on unattractive) and the scenes are covered with a blue haze. Clowe’s characters are as real as the issues they deal with, which in some ways make the story’s subject matter harder to take down. It is interesting that a novel like Batman, Watchmen, and even Jimmy Corrigan to some extent rely on lightness and jokes to discuss the serious underlying issues that drive the novels forward, but novels such as Ghost World, Night Fishers, or Shortcomings maintain a sort of realism about everyday (mostly relational) struggles that humans face.

One aspect of the book I found interesting was the reoccurring symbol of the words “Ghost World.” We see it tagged on signs and garage doors, and at one point, Enid even witnesses a graffiti artist that has left a fresh tag. “Come back here!” she yells. I haven’t yet decided what to make of this, but I suspect major themes of the book are reflected in such taggings.

Ghost World

Daniel Clowes’s “Ghost World” was a hauntingly beautiful book that reminded me much of “Black Hole”, but with a different, more subtle approach to the same ideas of isolation, sexual initiation and the pain of growing up, a lost generation… There is the same juxtaposition of monsters and the modern world in “Ghost World”, but it doesn’t have the magical-realism-overtness of “Black Hole”. Still, the protagonists take delight in the grotesqueries of their own suburb: the Satanists and a host of other bizarre-looking specimens, most of whom are men (Norman, Weird Al, Bob Skeetes, the man they trick at the diner, the homeless man, the alter ego David Clowes… here the incurable disease seems to be loneliness). Also, the image of the unfortunate Carrie Vandenburg and her neck tumor on page 23 is straight up Charles Burns. There was something similar in the methods of illustration between the two as well – a sharpness to the lines and white spaces. But I thought that the images in “Ghost World” seemed a little bit more pop arty, especially because of the unusual use of the teal tinting. Though this also had the effect that the panels were bathed in a sinister and sickly light, or as if the reader was watching the world through the Night Vision of a camera lens.

I fell a little bit in love with Enid and her disaffected pseudo-intellectualism, bizarre outfits, and self-loathing right from the beginning, but over the course of the novel I became more and more intrigued by the character of Rebecca. Though she is the more conventionally pretty one of the duo, and slightly more socially adroit, she fades into the background and bemoans the fact that “Deep down every single boy likes her [Enid] better!” (70). Her last name is repeatedly punned as “Doppelganger”, implying that she is a clone. Also, originally, the term “doppelganger” had a creepier meaning – a ghostly being that haunted its lookalike, and sometimes was a death omen for its human counterpart. This relates back to the ambiguous and eerie title of the book.

The title was an unsettling, unresolved aspect of the novel without a simple interpretation. As in everything else that we have read, there is a healthy dose of death in this comic – there is the hearse, and next to the table of contents we see a younger Enid and Rebecca standing in a cemetery (in front of the grave of Enid’s real mother?). The town where the two girls live is a dead one, a concrete one, overrun with strip malls and fast food restaurants. The 50’s diner that our protagonists frequent is itself a weak ghost – a pathetic replica of something long gone. Perhaps Clowes is drawing a parallel between himself and the phantom-like, anonymous artist in the book who runs around graffiti-ing walls and garage doors. The idea of scrawling over surfaces, the name Norman traced into the concrete panel, in a convoluted way relate back to a murky concept of what comics are – creating a static visual symbol and leaving some kind of mark on the surface of society.

Ghost World: It was really sad

Ghost World was a very sad book. The characters had so many good things in front of them and yet they did not appreciate what they had. If I had been in their position I would have been quite happy. For instance, the boy who Enid and Rebecca hang out with a lot is nice and they should have treated him nicer because that is what I thought he deserved. I was also quite confused by the ending because I did not know whether or not Rebecca and Josh were dating or not. Anyone have any ideas about this because I was totally lost. Also where is Enid going on the bus? It was almost like the author did not even try but instead just came up with random scenes and things to happen. It was so random like when Enid shaves her head and then it does not get brought up again. The colors I did not like at first, but they grew on me, especially when I noticed that the colored tiles in my kitchen (white and green) were the same color as the colors in the book (white and green).

If there was one thing I could have changed about the story though, it would be to make it a little happier. “Life is what you make it” as they say. I counted up the panels that I thought were happy and the ones I thought were sad and there were many more sad panels than the happy ones. I would like to suggest that next time this class is taught that in place of Ghost World we read something like Madeline (a graphic novel about young women), or Clifford Takes a Trip (a graphic novel about a bus ride), or Frog and Toad are Friends (a graphic novel about a frog, named Frog, and a toad, named Toad, who are friends). In my opinion they are all happy alternatives sure to put a smile on anyone’s face!

But that is not to say that the book was all bad. It definitely had some good moments that I did think represented my time in high school. For instance when Enid decides to get a hearse it made me think about when me and my friends all wanted to have hearses after we had watched Harold and Maude. It was also interesting how there was a character named David Clowes in the book and I wondered if Daniel Clowes was maybe making fun of his brother or something. Lastly the different things that would be playing on the television were sometimes really ridiculous and the way that the characters would talk about what was on the tv reminds me a lot of things my friends and I have said some of the stuff you see on tv. My friends and I did not hang out in cafes that much though because it is kinda expensive, so I am not sure how Enid and Rebecca could afford it.

I got Professor Chee’s e-mail (but I only had time to glance at it) and I guess he wants these to be more like Amazon.com reviews? So I guess I will just close by saying that I give this graphic novel a 2 stars out of 5. It probably would have gotten 3 or 4 stars if it had been a story about a “world” where “ghosts” live like I was expecting it to be.

Witty, Dark, and Real

“Daniel Clowes’ “Ghost World” is a sarcastic, witty novel, with a serious dark undertone. Following Enid, an 18-year old girl searching for her identity, the novel meanders about, presenting odd scenarios and characters, each adding a specific facet to the reader’s experience.

What I found impressive about Clowes’ work was his treatment of Enid’s character. The reader truly witnesses Enid grow and change throughout the novel; constantly altering her appearance, Clowes makes it quite clear just how desperately she is searching for a grasp on who she really is.

Thus, we have yet another novel dealing with many issues easily found during teenage years – sexual exploration, identity, future plans, and changing friendships. Rebecca, Enid’s seemingly more “normal” counterpart, undergoes a great deal of torment at the thought of her best friend leaving for Strathmore. The relationship the two share is an interesting one in that they are more than friends, more like “life partners” (save no sex, despite talk of “becoming lesbian”). As Enid prepares to leave, studying for her test, the obvious tension of their supposed upcoming separation manifests itself in arguments typically found in a serious romantic relationship. For instance, on page 57, the two fight over the fact that Enid hasn’t told Rebecca about her studying, which then leads to a much bigger argument. This seemingly simple admission is truly the breaking point for their friendship; from this point forward, the two rapidly move apart, fueled by faux anger and true heartbreak. Rebecca feels as though she is being left behind, and although she literally is, the fact is she is truly scared of what is to become of her without the friend she has come to rely upon.

In fact, this story is simply a transitional period in both of these young lives; in this short time span, the two go in completely different directions, representing how quickly life can change. Clowes, in a short 85 pages, takes these two women on an emotional rollercoaster as they seem to become entirely different people by the end of the novel. Ultimately both Rebecca and Enid are searching for their place, or at least a point where they feel comfortable with who they are.

What’s difficult about this novel is how realistic each element is. Not unlike “Night Fisher”, Clowes’ work forces the reader to cope with situations that are easy to imagine, for on some level, we have all experienced them in one manner or another. The rejection that Rebecca feels is understandable, and the fear that Enid experiences (and the subsequent anger and slightly pompous attitude) is equally imaginable. Thus, Clowes creates a novel that deals with real issues in real ways. I found this to be refreshing, as this story was simply a story; no monsters, no diseases, no superheroes, just realistic situations presented through this dynamic teenage relationship.

We have read such a wide variety of novels, each which portrayed situations, ideals, problems, etc in different manners. What has become apparent to me is that even novels like “Watchmen”, a seemingly completely different comic than “Ghost World”, all share such similar elements. These comics allow their readers to experience real situations in such a different, and in many respects, a more connective manner than a typical novel. This is a fact that I didn’t realize until now, but ultimately, it has made me realize just how powerful a comic can be.

Surprising Realsim

With a title like Ghost World, I fully expected some strange, supernatural twist from Daniel Clowes’s comic. And yet his story was completely based within the real-world, day-to-day lives of young women dealing with real-world, day-to-day issues: boys, sex, gossip, friendship, jealousy, growing up, betrayal, change.

My initial reaction to the main character’s Enid and Rebecca – especially their language and dialogue – was that their persons and syntax were unrealistic. “I never talked like that,” I though, “and I don’t talk that way now either.” However, upon looking at Clowes’s dialogue a second time, and paying closer attention to the ways that I spoke with my friends at lunch, at parties, or when hanging out (and also eavesdropping on some other Valentine conversations) I realized that Enid and Rebecca’s way of talking to each other was actually alarmingly similar to discussion in daily life (although Enid is more liberal with her profanity than most of the people I spend time with).

I began to wonder what it was about this comic that initially made it seem so unreal to me, despite the truth of its writing. From the you-know-I’m-your-friend-so-I-can-say-mean-things-to-you-and-get-away-with-it quality of Enid and Rebecca’s exchanges (Rebecca: “You’re a stuck-up prep-school bitch!” Enid: “Fuck you!” p.9) to the off-handed, non-politically correct comments shared between friends (Enid: “God, don’t you just love it when you see two really ugly people in love like that?” p.25), Clowes’s characters are undeniably realistic. What makes it difficult to initially see this realism is the fact that it is so blatantly displayed in this dialogue-heavy comic. Real-life conversations sound utterly fake when they are written down; the unavoidability of these conversations in Ghost World makes them feel like they should be constructed dialogue, and yet they are not.

Another aspect of Clowes’s work that adds to this realism is that way that characters are drawn. Their clothing changes day-to-day, their hair grows (or gets cut and dyed green), they get new glasses. Even small details add to the realism, like Enid’s safety pin earring that she wears when she “goes punk.”

One small element that I found very interesting was Clowes’s inclusion of himself in the comic. This first happens on page 26 when Enid cites Clowes as the “one guy who lives up to [her] standards,” becoming very oddly meta as his character in his comic says of his work that “these aren’t like normal cartoons …” Enid quickly changes the subject, taking it away almost as quickly as it is come up (again, not an uncommon part of normal conversation). I at first thought the comic was going to become a strange contemplation of Clowes’s work, but he was only mentioned once more. Yet his part in the story lingers in an odd way such that the comic becomes removed form itself; the characters exist independent of their creator. Or are they figments of his imagination without knowing it? Do they exist in a “Ghost World” within his imagination? It is interesting to contrast Clowes’s presence in Ghost World to the small comic on the back of Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan; while Ware is undeniably self-deprecating and emphasizes that no one wants to read his book, Clowes calls himself “famous.”

I have not seen the film version of Ghost World, and I’m not sure that I want to. I think one of the greatest strengths of the comic is its ability to mirror real speech with off-putting accuracy, forcing the reader to contemplate it through the process of reading. Hearing the speech spoken would take away from the jarring “wow, that really is how many young adults talk” quality of the story.

Ghost World

Yeah, I read the book. No, I have no idea what to think about it. What does this mean? What is Daniel Clowes attempting to get at here? Going through everyone else’s posts (which I enjoyed, by the way) I came across this section of Athena’s post:

“Ghost World” is about growing up, and growing up is painful. So how else should one portray it? Enid and Rebecca hate most everything and everyone—but they’re intelligent and interesting, and they live in a place that has not offered them much in the way of culture. How else should they react? What I like about “Ghost World” is that it’s real.

Yeah, that’s how I feel too! Thinking about it, I realized that regardless of whether we like or dislike the book or the characters, they are so very real. The book as a whole is terribly painful, especially as we watch the relationship between Enid and Rebecca completely dissolve before their eyes and ours. The reality comes from the stark, urban setting as well as the conversation between the two teenage girls. We constantly come across the same graffiti, over and over again, as new scrawlings of the title pop up on brick walls, garage doors, and windows. As Rebecca says: “God, how long has that graffiti been there?” (63) Reality also comes through for us at the end: Enid Coleslaw will not go to college. Rebecca will not go with her, but neither will the two of them continue their friendship just as it always was. Through the Josh Episode (as I’m sure they would call it, with some extra elective describing his gayness or dork-ness or whatever) and their own confusion about the future, their friendship fractured irreparably.

The moments of real growth for Enid occur after the Josh Episode and after she buys the hearse. Her father announces that he’s going on a date with Carol, “THE Carol?,” one of his ex-wives. Enid, sitting in front of him, looks him straight in the eye and says in typical Enid-fashion: “What the fuck are you DOING?“ (69) Yes, she’s mouthy and sarcastic and clearly unafraid of authority, but this feels different. She seems to be looking out for her dad’s well-being, something very grown-up and different than her usual. Then, in the hearse on the way back from their practice trip to Swarthmore, Enid tells Becky that her secret plan was to leave town forever and not tell anyone, just become this totally new person. Becky tells her that she doesn’t understand. Enid replies, “THat’s because you don’t utterly loathe yourself…” (75) What better indication of growing up than learning that you don’t like parts of yourself? Enid is starting to really discover herself, the parts she likes and the parts she doesn’t, a painful process that will bring more pain as it separates her from Becky even further.

For me, the best part of the book was the end. Somehow, Clowes has managed to make this part feel so much more grownup than the beginning. Perhaps it is Enid’s hair, loose and barrette-free for the first time. Perhaps it is her outfit, with no sense of the punk-rock/”to defy definition” style that she once had. (68) Whatever it is, we follow Enid through the town she grew up in. Strangely enough, when she encounters fresh “Ghost World” graffiti, she calls out to the perpetrator: “Hey! Hey! Come back here!” (79) Is she conforming to society’s laws, trying to disrupt an illegal activity? Or does she want an answer to a great childhood question? Spotting Becky in a diner window, Enid says “You’ve grown into a very beautiful woman.” (80) Then she walks onto the bus, we assume off to a new town to build a new identity, just as she always secretly planned. This very mature and grown-up final interaction between the two (ex)friends gives Enid and the reader closure, and shows us just how grown-up Enid’s really become.